|

|

My mother's maternal grandparents. |

|

My mother's parents Sarah and Lewis Adler April 23, 1944 |

|

My father's parents, Henry and Rebecca Brilliant, Nov. 14, 1942. |

|

My parents, Amelia and Victor Brilliant, August

28 1957 (their 25th wedding anniversary). |

|

My sister, Myrna Brilliant, (my only sibling). 1959 (?) |

|

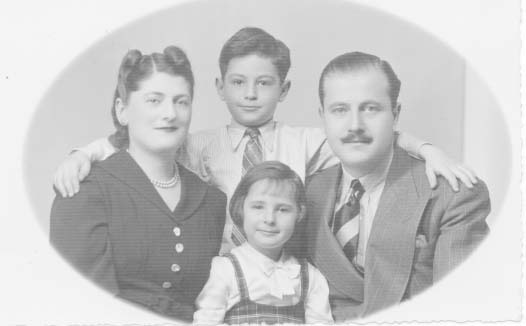

| Here I'm with my mother, sister, and my mother's brother Marsh Adler. Toronto 1940 |

Ashleigh Amelia Victor Myrna London, 1949

The following was written by my father to his family in England:

…………………….

The

first five days out were like a pleasure cruise and worth £50

in itself, and by that time we had only got as far as Cape Wrath.

It was a "Cargo-passenger" boat, and the accommodation

for the four of us was marvelous; the food was also perfect, likewise

the weather. I can't go into details about convoys, etc., but

at 7 p.m. on the 20th of May we were torpedoed without warning.

Now everything might have been alright if we hadn't had a native

crew (five Malays and 30 odd Indians) with white officers, of

course. I went on deck after the explosion (with much confusion

in the ship) and could see it wouldn't sink in five minutes. I

went back to my cabin twice to gather a few things, but all the

lights had gone and the glass smashed, and everything thrown about,

with the fire extinguishers burst and the stuff all over the place

and water and oil all about. - We weren't far from the engine

room where the torpedo had gone clean through, -- and I brought

my suitcase and attaché case up on the boat deck leaving

everything I had out in the cabin, and, of course, two large trunks

nearby. I had put on my overcoat and a cap, realizing that we

might be all night in the open boat and I also put on a lifebelt,

but when I got on deck there was confusion. The native crew had

panicked and were hacking at the boat ropes and scrambling down

ropes over the boat's sides; one boat was nearly lost by being

dropped straight into the water, but was recovered. There was

a high sea running, and my boat was on the weatherside of the

ship. I was the only one of the four passengers to get into the

right boat, but only by good fortune was I saved at all. There

were no ropes available, for the boat and rope ladders were not

in the right place; the position was as under:

"A" marks

the position where I got down the rope ladder; I was almost the

last to leave the ship which was already sinking by the stern.

Horowitz had gone down by the rope ladder "A", and I

followed. The boats were tossing about like corks, and couldn't

get near the ladders. After Horowitz had gone, I looked round,

and found I couldn't reach the boat "X", and they didn't

seem to bother about me. They had their work cut out to keep the

boat itself safe, i.e. the few white officers. If you've never

hung on to a rope ladder, you won't know what I experienced; your

feet go forward, and you hang on your hands! Well, when I could

hang on for very little longer, I was already saying "goodbye"

because even had they been able to pick me up in the boat, I should

never have survived it. I shouted in desperation for a rope and

the 3rd officer managed to get one near which I hooked with one

arm, and had to cling to the rope ladder again for "dear

life". You can imagine me hanging on the end of this ladder,

swaying in a strong wind being buffeted against the side of the

sinking ship with nothing near me and 1000 fathoms of ice-cold

water beneath me. I shouted for them to hang on to the end of

the rope and I quickly made the "plunge", i.e. I slid

somehow along this rope and landed somehow or other in the boat,

being wet only up to my calves. I had to abandon my two cases

on the boat deck as I considered I'd be lucky to get away with

my life. Well, then our troubles started. First of all I looked

for Horowitz and found he was in the water and trying to get into

the boat. I found out afterwards what had happened; he had made

a leap for the boat in one of its "surges" towards us,

had missed, and gone into the water, but had managed to get hold

of the painter rope or whatever it was, and had pulled himself

round, but they couldn't pull him in. His overcoat being soaked

with water weighted him. I hung on to him but had no strength

in my arms at all after my ordeal - it was surprising to me how

weak my hands and arms were; however, I called to one of the engineers

with us and together we all managed to get him in. He was going

to let go as he couldn't hang on any longer but I did my best.

Then my two fears were that the boat would get smashed against

the jagged edge of the ship made by the torpedo; against this

hole and edge we were being dashed and couldn't manoeuvre; I was

also afraid of not getting away in time before the ship sank and

drew us down with it. I managed to grab an oar and help to keep

the boat away. The oars were all tied up and couldn't be got at

and the crew were immobile and we couldn't shift; there was no

rudder fixed on the boat and we weren't sure whether the bung

was even in. Well, at last we got away and did it toss and pitch

like a cork, in a high sea; we were down in a trough one minute

and up again the next. Horowitz was nearly frozen, the weather

wasn't cold but the water was icy - I got drenched on one side

and became almost numb. I gave H. a swig of spirits. (When on

deck, before leaving, I unlocked my case, took out my passport

and a few papers, and a small bottle of spirits which I'd kept

for such a purpose, believe it or not). An officer gave him his

life jacket to keep covered with and he was better and emptying

himself of water. (Even with his lifebelt he'd swallowed and enormous

amount). And then the Malay sitting facing me (I was in the stern)

was sick as a dog - partly over me, and then I started for the

first time in my life; and I was ill! The four lifeboats had got

separated and we took out the compass, tho' how the dickens they

could do anything by that I don't know. However, even before we

were in the boats we could see a destroyer in the distance, which

had been convoying, and which convoy we'd passed only that morning,

so we knew we had a good chance when we were hit; but it didn't

pick us up. No, its job was to go for the submarine, and a depth

charge nearly blew us out of the water. Three-quarters of an hour

after being hit, we saw the ship go down - about half a mile away;

it turned slowly bows up, and with a hiss of steam at the water-line,

it dived straight down. At the outset they had to put an officer

in each boat to stop the crew getting away with them and leaving

the rest of us. The Captain took the fourth passenger into his

boat instead of the right one; he was the only one who was armed

as the rest of the stuff was locked up. So there were three of

us passengers in one boat and the fourth in another. We were picked

up by a R.N. Corvette after a struggle in that rough sea; the

other two boats (including the fourth passenger) were picked up

by a tug. And what a time we had on board! At least I was fairly

well after twenty-four hours but the others were ill the whole

time. The boat rocked and tossed like a cork, ask anyone what

a Corvette is like even in a fairly calm sea. I was ill and sick

on board and crawled into a corner and sat on a camp stool, wet

as I was. Well, I'll cut out a lot of the details here. The officers

were splendid; after a little time I settled down, gave my clothes

to dry and wore borrowed clothes. We had the officers' cabins

and bunks, and they slept on the floor somewhere; the accommodation

on these ships is bad. We spent a day and two nights on board.

All the officers, crew and passengers rescued were sick as possible

- and we had had no dinner before it happened.

They intended transferring us to a rescue vessel and taking us

back to Scotland or Iceland; in fact, all the officers and crew

were dispatched to Scotland. I, however, made representations

to the Captain and asked for a transfer to a westward bound ship

of the convoy; he got in touch with the Commodore of the escort

vessels, and after a signal palaver and various questions, the

transfer was arranged. With me came the other two passengers,

but they had to signal to the tug for the 4th passenger (who was

part of a "team" with the 3rd) for his transfer, too!

(Incidentally, after being rescued, it took them about 15 hours

to pick up the convoy again). Well, about 9 a.m., all was set,

when we had warning of an air attack imminent. Fortunately it

turned misty and began to rain as well, and in this they manned

a boat (we got in first this time) and lowered us. But in that

sea it was no joke; the previous evening we had the choice of

going then or waiting till the morning. As the sea was very rough

the others wanted to wait, though I'd have gone then in order

to get away from that ship; but one of them was ill and couldn't

move. Well, on lowering the boat with a bang, I got hit on the

head with an oar, and the other passenger got hit with the iron

end of a rope, but we managed to be taken aboard; we had lifelines

thrown to us; one man it slipped, the second got caught and nearly

pulled into the sea (this was H. and he got a wetting in part

again) and I managed O.K.

We were on board this cargo-passenger ship for 9 days before we

reached Halifax, and you can imagine it was no picnic without

a brush or a razor or anything at all between us. There happened

to be a very small lounge which they converted into a dormitory

for us; we slept on trestle beds almost touching each other, and

no ventilation owing to the black-out. Nevertheless, the catering

was good, and we stuck it out well. Even so, we had plenty of

scares, and we slept in our clothes for about a fortnight altogether.

There are quite a number of things I can't mention in this letter,

but you can be sure we were more than glad when we reached Halifax,

where I landed for a few hours, cabled you, phoned Washington,

and phoned Amel who wrote to you the same night. We had the Commodore

of Convoy on board and we had to land him at Halifax. Here they

had to make special arrangements for me to continue with the boat

to New York, the others had gone by plane. I had the Commodore's

cabin, but you'll see that I never slept there. On the way to

New York, early the first night, we had foggy weather…………………………………………but

I was bad the following night. In fact, I didn't sleep for 3 nights

and didn't eat or drink at all for 36 hours. Naturally, when I

landed at Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, I was worn out, although I'd had

easier spells. We had to remain in New York Harbour 24 hours before

landing. I had been through all sorts of climates since embarking

in England, from icy cold to heat wave, and through gales - one

exceptionally bad. We'd been traveling all directions and zig-zagging,

etc.; I spent only a few hours in New York, and I was anxious

to get to Toronto (I had made arrangements by 'phone with Washington

to spend a week there), so I didn't make any family calls, etc.,

especially the way I felt and looked - being a survivor. I traveled

overnight to Toronto, which meant another almost sleepless night,

and arrived in the morning almost utterly exhausted though relieved

to be there at last. Marsh had got on the train at Sunnyside (the

station before) and found me on the train. ……………………………………………………………………………..

……………………………………………………………………………………………

##